2 Tossing Function

2.1 Introduction

In the previous chapter we wrote code to simulate tossing a coin multiple times.

First we created a virtual coin as a two-element vector. Secondly, we discussed

how to use the function sample() to obtain a sample of a given size, with and

without replacement. And finally we put everything together: a coin object

passed to sample(), to simulate tossing a coin.

# tossing a coin 5 times

coin <- c("heads", "tails")

sample(coin, size = 5, replace = TRUE)

#> [1] "tails" "heads" "tails" "tails" "tails"Our previous code works and we could get various sets of tosses of different sizes: 10 tosses, or 50, or 1000, or more:

# various sets of tosses

flips1 <- sample(coin, size = 1, replace = TRUE)

flips10 <- sample(coin, size = 10, replace = TRUE)

flips50 <- sample(coin, size = 50, replace = TRUE)

flips1000 <- sample(coin, size = 1000, replace = TRUE)As you can tell, even a single toss requires using the command

sample(coin, size = 1, replace = TRUE) which is a bit long and requires some

typing. Also, notice that we are repeating the call of sample() several times.

This is the classic indication that we should instead write a function to

encapsulate our code and reduce repetition.

2.2 A toss() function

Let’s make things a little bit more complex but also more interesting. Instead

of calling sample() every time we want to toss a coin, we can write a

dedicated toss() function, something like this:

# toss function (version 1)

toss <- function(x, times = 1) {

sample(x, size = times, replace = TRUE)

}Recall that, to define a new function in R, you use the function function().

You need to specify a name for the function, and then assign function() to the

chosen name. You also need to define optional arguments, which are basically the

inputs of the function. And of course, you must write the code (i.e. the body)

so the function does something when you use it. In summary:

Generally, you give a name to a function.

A function takes one or more inputs (or none), known as arguments.

The expressions forming the operations comprise the body of the function.

Usually, you wrap the body of the functions with curly braces.

A function returns a single value.

Once defined, you can use toss() like any other function in R:

# basic call

toss(coin)

#> [1] "tails"

# toss 5 times

toss(coin, 5)

#> [1] "heads" "tails" "heads" "tails" "tails"Because we can make use of the prob argument inside sample(), we can make

the toss() function more versatile by adding an argument that let us specify

different probabilities for each side of a coin:

# toss function (version 2)

toss <- function(x, times = 1, prob = NULL) {

sample(x, size = times, replace = TRUE, prob = prob)

}

# fair coin (default)

toss(coin, times = 5)

#> [1] "heads" "heads" "heads" "tails" "tails"

# laoded coin

toss(coin, times = 5, prob = c(0.8, 0.2))

#> [1] "heads" "heads" "heads" "tails" "heads"2.3 Documenting Functions

You should strive to always include documentation for your functions. In fact, writing documentation for your functions should become second nature. What does this mean? Documenting a function involves adding descriptions for the purpose of the function, the inputs it accepts, and the output it produces.

Description: what the function does

Input(s): what are the inputs or arguments

Output: what is the output or returned value

You can find some inspiration in the help() documentation when your search

for a given function: e.g. help(mean)

A typical way to write documentation for a function is by adding comments for things like the description, input(s), output(s), like in the code below:

2.4 Roxygen Comments

I’m going to take advantage of our toss() function to introduce Roxygen

comments. As you know, the hash symbol # has a special meaning in R: you use

it to indicate comments in your code. Interestingly, there is a special kind of

comment called an “R oxygen” comment, or simply roxygen comment. As any R

comment, Roxygen comments are also indicated with a hash; unlike standard

comments, Roxygen comments have an appended apostrophe: #'.

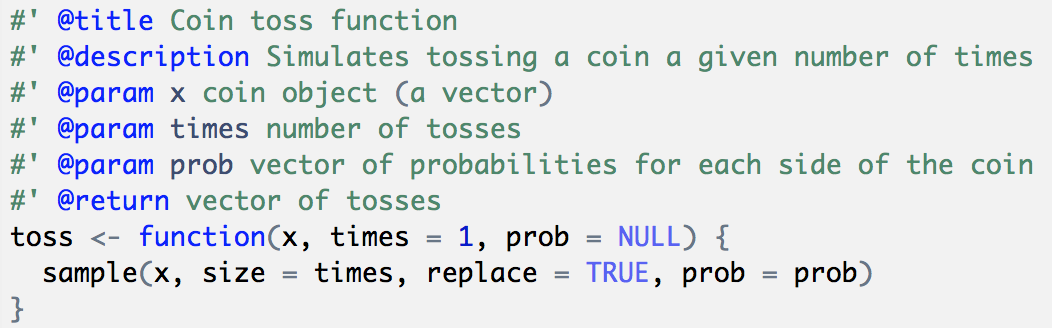

You use Roxygen comments to write documentation for your functions. Let’s see an example and then I will explain what’s going on with the roxygen comments:

#' @title Coin toss function

#' @description Simulates tossing a coin a given number of times

#' @param x coin object (a vector)

#' @param times number of tosses

#' @param prob vector of probabilities for each side of the coin

#' @return vector of tosses

toss <- function(x, times = 1, prob = NULL) {

sample(x, size = times, replace = TRUE, prob = prob)

}If you type the above code in an R script, or inside a coce chunk of a dynamic

document (e.g. Rmd file), you should be able to see how RStudio highlights

Roxygen keywords such as @title and @description. Here’s a screenshot of

what the code looks like in my computer:

Figure 2.1: Highlighted keywords of roxygen comments

Notice that each keyword of the form @word appears in blue (yours may be in a

different color depending on the highlighting scheme that you use). Also notice

the different color of each parameter (@param) name like x, times, and prob.

If you look at the code of other R packages, it is possible to find Roxygen

documentation in which there is no @title and @description, something like

this:

#' Coin toss function

#'

#' Simulates tossing a coin a given number of times

#'

#' @param x coin object (a vector)

#' @param times number of tosses

#' @param prob vector of probabilities for each side of the coin

#' @return vector of tosses

toss <- function(x, times = 1, prob = NULL) {

sample(x, size = times, replace = TRUE, prob = prob)

}When you see Roxygen comments like the above ones, the text in the first line

is treated as the @title of the function, and then the text after the empty

line is considered to be the @description. Notice how both lines of text have

an empty line below them!

The @return keyword is optional. But I strongly recommend including @return

because it is part of a function’s documentation: title, description, inputs,

and output.

2.4.1 About Roxygen Comments

At this point you may be asking yourself: “Do I really need to document my

functions with roxygen comments?” The short answer is No; you don’t. So why

bother? Because royxgen comments are very convenient when you take a set of

functions that will be used to build an R package. In later chapters we will

describe more details about roxygen comments and roxygen keywords. The way we

are going to build a package involves running some functions that will take the

content of the roxygen comments into account and use them to generate what is

called Rd (R-dcoumentation) files. These are actually the files behind all

the help (or manual) documentation pages of any function.